|

FAQ

Frequently Asked Questions

- What is a netsuke?

- Are there different types of netsuke?

- Aren't all netsuke made from ivory?

- Are all netsuke signed?

- Where can I see netsuke?

- What are the best books on netsuke?

- Where can I buy books on netsuke?

- Where can I buy netsuke?

- Are there fake netsuke?

- Don't the Japanese own all the great netsuke?

- What factors are involved when buying netsuke?

What is a netsuke? (pronounced “nets-keh”)

A netsuke is a small sculptural object which has gradually developed in Japan over a period of more than three hundred years. Netsuke (singular and plural) initially served both functional and aesthetic purposes. The traditional form of Japanese dress, the kimono, had no pockets. Women would tuck small personal items into their sleeves, but men suspended their tobacco pouches, pipes, purses, writing implements, and other items of daily use on a silk cord passed behind their obi (sash). These hanging objects are called sagemono. The netsuke was attached to the other end of the cord preventing the cord from slipping through the obi. A sliding bead (ojime) was strung on the cord between the netsuke and the sagemono to allow the opening and closing of the sagemono.

The entire ensemble was then worn, at the waist, and functioned as a sort of removable external pocket. All three objects (netsuke, ojime and the different types of sagemono) were often beautifully decorated with elaborate carving,  lacquer work, or inlays of rare and exotic materials. Subjects portrayed in netsuke include naturally found objects, plants and animals, legends and legendary heroes, myths and mystical beasts, gods and religious symbols, daily activities, and myriad other themes. Many netsuke are believed to have been talismans. These items eventually developed into highly coveted and collectible art forms. Today we see a broad range from “folk art” carvings to levels of sophistication some consider to be fine art.

lacquer work, or inlays of rare and exotic materials. Subjects portrayed in netsuke include naturally found objects, plants and animals, legends and legendary heroes, myths and mystical beasts, gods and religious symbols, daily activities, and myriad other themes. Many netsuke are believed to have been talismans. These items eventually developed into highly coveted and collectible art forms. Today we see a broad range from “folk art” carvings to levels of sophistication some consider to be fine art.

With transition to European dress, the use of sagemono and netsuke declined, nearly disappearing over the period from the end of 19th to the first quarter of the 20th century but the production of netsuke did not completely go away. Instead, under a strong influence of Western collectors visiting Japan in larger and larger numbers, netsuke developed into a form of fine art and exists as such today with true master-carvers from all over the world still creating these little masterpieces. Unfortunately, the souvenir industry both in Japan and abroad stimulated production of low artistic value mass-produced figurines mimicking the real netsuke to satisfy the growing tourist demand. Those netsuke-like objects should not be confused with the authentic art pieces regardless of their age and origin.

Are there different types of netsuke?

Yes, with the most common being the katabori or figural netsuke. Manju netsuke are named after a popular bean paste confection that came in a round, flat shape. Kagamibuta (literally, "mirror lid") are a special type of netsuke with a metal lid and a bowl, usually of wood or ivory. Mask netsuke, were carved as miniature versions of the masks used in Noh and Kyogen plays. There are also sashi or long, thin netsuke, that were thrust through the belt, with the sagemono suspended from the end that protrudes from the obi

Types of Netsuke

Katabori Netsuke

Examples of katabori netsuke

kataborinetsuke or "sculpture netsuke" - this is the most common type of netsuke. They are compact three-dimensional figures carved “in the round”, and are generally about one to three inches high.

Anabori Netsuke

anaborinetsuke or "hollowed netsuke" – a subset of katabori which are carved out for a hollow center. Clams are most commonly the motifs for this type of netsuke. Elaborate scenes may comprise the interior.

anaborinetsuke or "hollowed netsuke" – a subset of katabori which are carved out for a hollow center. Clams are most commonly the motifs for this type of netsuke. Elaborate scenes may comprise the interior.

Manju Netsuke

manjunetsuke or "manju netsuke"- a thick, flat, round netsuke, with carving usually done in relief, sometimes made of two ivory halves. Shaped like a manju, a Japanese confection.

Front and back of a manju netsuke

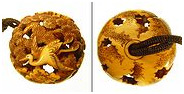

Ryusa Netsuke

ryusanetsuke - shaped like a manju, but carved like lace, so that light is transmitted through the item.

Kagamibuta Netsuke

kagamibutanetsuke or "mirror lid netsuke" - shaped like a manju, but with a metal disc serving as lid to a shallow bowl, usually of ivory or sometimes wood. The lid is often highly decorated with a wide variety of metallurgical techniques.

kagamibutanetsuke or "mirror lid netsuke" - shaped like a manju, but with a metal disc serving as lid to a shallow bowl, usually of ivory or sometimes wood. The lid is often highly decorated with a wide variety of metallurgical techniques.

Obi-hasami Sashi Netsuke

sashinetsuke - an elongated form of katabori, literally "stab" netsuke, similar in length to the sticks and gourds used as improvised netsuke before carved pieces were produced. They are about six inches long.

Obi-hasami - another elongated netsuke with a curved top and bottom. It sits behind the obi with the hooked ends visible above and below the sash.

Mask Netsuke

mennetsuke or "mask netsuke" - the largest category after katabori, these were often imitations of full size Noh, Bugaku or Kyogen masks, and share characteristics in common with both katabori and manju/kagamibuta.

mennetsuke or "mask netsuke" - the largest category after katabori, these were often imitations of full size Noh, Bugaku or Kyogen masks, and share characteristics in common with both katabori and manju/kagamibuta.

Trick Netsuke

karakurinetsuke or "trick/mechanism netsuke" - any netsuke that has moving parts or hidden surprises.

Aren't all netsuke made from ivory?

No, that is a common fallacy. Perhaps only half of all netsuke are ivory. Netsuke-shi (netsuke carvers) used the materials that were available. Mainly artists located in Osaka, Kyoto, and Edo (Tokyo) had access to ivory in the old days. Artists outside of these population centers primarily used box or cherry wood, which they stained and polished. However, nearly every material imaginable was used, including almost 100 types of wood, killer whale teeth, narwhal and walrus tusk (marine ivory), boar's tusk, amber, stag antler, pottery, bamboo, coral, etc. Below is a brief list and descriptions of some of these materials.

Materials Used:

-

ivory - one of the most common materials used before ivory from live animals became illegal. Netsuke made from mammoth ivory (huge quantities still exist in the Near East and Siberia) fill part of the tourist trade demand today. (Mammoth ivory is old ivory, 10,000-25,000 years, the carvings themselves are almost all of very recent production)

-

boxwood, other hardwoods - popular materials in Edo Japan and still used today

-

metal - used as accents in many netsuke and kagamibuta lids

-

hippopotamus tooth - used in lieu of ivory today

-

boar tusk - mostly used by the Iwami group of carvers

-

rhinoceros horn

-

hornbill ivory - a rarely used material

-

clay/porcelain

-

lacquer - many were by the same makers of lacquer inro

-

cane (woven)

Unusual materials used in netsuke:

Hornbill ivory: Of the many varieties of hornbill, only the helmeted hornbill (Buceros vigil or Rhinoplax vigil) furnishes an ivory-like substance. This is a dense substance found in the solid casque growing above the upper mandible (the bird’s forehead). Structurally, it is not ivory, horn, or bone, yet it has been called ivory for many centuries. It is softer than real ivory and is a creamy yellow in color, becoming red at the top and sides. This feature can be used for highlights in a carving.

Umimatsu: The literal translation is “seapine”. It is in fact a species of black coral with dense texture, concentric growth rings, and amber or reddish colored inclusions in the otherwise brown-black material. True coral, however, is a hard calcareous substance secreted by marine polyps for habitation. Umimatsu, on the other hand, is a colony of keratinous antipatharian marine organisms. As a material, it is more acceptable to collectors than carvers as it was prone to crack, crumble or chip. Carvers find that it is risky for carving details and subtle effects.

Umimatsu was also used as inlays for eyes, buttons, etc.

Umoregi: There are several definitions, some contradictory. It has been called a partially fossilized wood, having the general appearance of ebony but showing no grain. Also often called fossilized wood, umoregi is not properly a wood, but a "jet" (a variety of lignite), that is often confused with ebony in appearance. It is a shiny material that takes an excellent polish but it has a tendency to split. Umoregi-zaiku is petrified wood formed when cedar and pine trees from the Tertiary Age (5 million years ago) were buried underground and then carbonized. The layers of earth where umoregi-zaiku can be found extend under the Aobayama and Yagiyama sections of Sendai, Japan. Pieces made from this material are generally very dark brown with the soft luster of lacquer.

Walrus tusk: Walrus have two large tusks (elongated canine teeth) projecting downward from the upper jaw. These tusks, often reaching two feet in length, have been extensively carved as ivory for centuries in many countries and especially in Japan. Walrus tusk carvings are usually easy to identify, because much of the interior of the tooth is filled with a mottled, almost translucent substance that is harder and more resistant to carving than the rest of the tooth. Manju, especially ryusa manju, invariably show this translucent material at opposite edges of the netsuke.

Whale's tooth: The sperm whale has teeth running the whole length of its enormous lower jaw. Those in the middle tend to be the largest, often obtaining a length of more than six to eight inches. Often used elsewhere by carvers of scrimshaw, a large tooth could be used to produce several netsuke.

Whale bone: All bones are hollow, the cavity being filled with a spongy material. Cuts across some bone show a pattern of minute holes looking like dark dots. Lengthwise, such bone displays many narrow channels which appear to be dark lines of varying lengths. Polished, bone is more opaque and less shiny than ivory.

Teeth: A variety of other teeth are used for netsuke, including: boar, bear, and even tiger.

Tagua nut: The nut from the ivory palm (Phytelephas aequatorialis), often referred to as vegetable ivory. Part of the nut’s shell sometimes remains on netsuke carvings. Though often mistaken for or deceptively sold as elephant ivory, items made from the two-to-three-inch nut have none of the striations common to animal ivory, and sometimes the ivory-like nut flesh has a light yellow cast under a rough coconut-shell-like external covering. The nut is very hard when dry, but easily worked into artistic items when wet.

Walnut (kurumi): The meat from the nut was removed by various means, one being the insertion of a small worm in a hole in the nut to consume the meat. Following that, elaborate designs could be carved in the shell and the cord inserted. The carver often removed all of the nut's normal surface features and carved through the surface in places to create a latticed effect. Once carved, the resulting netsuke was polished and shellaced.

Bamboo: Iyo bamboo is occasionally used for netsuke. Bamboo netsuke are carved from either a piece of the stem or the root. Carvings in the round are usually made from the underground stem portion of the plant, the small almost solid zone that connects to the creeping rhizome below the ground. Bamboo netsuke are not commonly encountered. Occasionally, one comes across a netsuke fashioned from bamboo root which can reveal the wonderful texture of the material.

Are all netsuke signed?

No, there are many unsigned netsuke. In fact, some of the netsuke considered by many experts to be among the greatest are unsigned. Among them are the netsuke frequently referred to as the Meinertzhagen Kirin after its first official Western owner, and a famous ivory netsuke depicting an Ama (Japanese diving girl) and a squid. Some collectors prefer unsigned works, since they avoid the controversy of whether the work is by a famous artist, a pupil or later follower of that artist, or just a copy.

Where can I see netsuke?

A number of Museums around the world have netsuke collections. Some of the finest collections can be viewed in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, National Art Museum in Tokyo, British Museum and Victoria and Albert Museums in London.

In the United States, the LACMA has a permanent exhibition of 150 netsuke from the Raymond and Frances Bushell collection. There are a total of 600 netsuke in the collection, which are regularly rotated into the exhibition.

The British Museum in London also has a permanent exhibition of netsuke from the A.H. Grundy collection.

Many other museums, including the Metropolitan Museum in New York, the Louvre in Paris, the Hermitage in St. Petersburg, have netsuke collections but they usually exhibit just a few at a time.

Unfortunately, due to the small size of netsuke, their display for public viewing is always a challenge so is not done often. Also, due to a relatively late recognition of netsuke as an art form, most of the museum collections were formed based on a number of previously assembled prominent private collections of the time, and therefore may be limited in size and scope by the personal tastes of the original owners.

Some believe the best netsuke masterpieces are still in private collections. Fortunately, some of those major collections are periodically made available for viewing and handling to the INS members by their generous owners. Also, due to the significant number of netsuke periodically changing owners through major art auctions, such as Bonham's, Christie's and in the past Sotheby's, a large number of images with corresponding sales prices can be accessed through their electronic archives.

In the United States, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art has a permanent exhibition of 150 netsuke from the Raymond and Frances Bushell collection. There are a total of 600 netsuke in the collection, which are regularly rotated into the exhibition. Numerous United States museums have netsuke collections, but they usually exhibit just a few at a time. The British Museum in London also has a permanent exhibition of netsuke from the A.H. Grundy collection. Please click here to visit our museums page for more links.

What are the best books on netsuke?

Today there is a wealth of good books, with beautiful illustrations, on netsuke. Two good works for beginners, both by Raymond Bushell, are An Introduction to Netsuke and The Wonderful World of Netsuke. Two volumes, which provide a comprehensive look at netsuke, are Netsuke by Neil K. Davey and Collectors' Netsuke also by Bushell. Raymond Bushell has also adapted the most basic work in Japanese on netsuke, The Netsuke Handbook of Ueda Reikichi. Finally, for those collectors interested in reading signatures, there is Netsuke and Inro Artists and How to Read their Signatures by George Lazarnick. Serious collectors always have extensive libraries which also include catalogs of special exhibitions of dealers, museums, and auctions. The Forum on this INS website also includes book recommendations as a dedicated topic which is added to periodically.

Where can I buy books on netsuke?

Three Asian art book dealers have Web sites. They are Paragon Book Gallery Ltd., Han-Shan Tang Books, and Rare Oriental Book Company. Please take a look at our book recommendations by clicking here.

Where can I buy netsuke?

Art Dealers: A special group of Asian art and antiques dealers who focus especially on netsuke and sagemono are among the members of the International Netsuke Society. Many of them exhibit at the International Netsuke Society Conventions.

Auctions: Two of the world's largest auction houses, Christie's and Bonhams have regular Japanese art auctions, often featuring netsuke, in London, New York, and San Francisco. There are also a variety of smaller auction houses in the United States and Europe that have Asian art auctions, many with netsuke, at least once a year. Please click here for a listing of auction houses.

Are there fake netsuke?

Due to the collectability of netsuke there are many fakes (or “netsuke-like carvings”) available in the marketplace. Many of these objects can clearly be seen as modern mass produced items to the trained eye while others are more difficult to discern as fakes. Crude modern copies, frequently referred to as "Hong Kong" netsuke, either in ivory or plastic, can be sold for as much as a few hundred dollars in souvenir shops and antique malls. There are also good modern copies of 18th and 19th century works, meant to defraud and sold for thousands of dollars. Finally, there are 19th century copies of earlier works that were carved by the Japanese to meet the demand from European collectors. These are excellent works of art but the difference in value between these copies and the original items can be a factor of ten or more.

Low quality tourist type netsuke, better referred to as netsuke-like carvings, frequently have meaningless squiggles carved to appear as legitimate signatures or a Japanese sounding name dictated by the factory where produced. Some of these carvings actually use poor reproductions of famous artists’ mei (signatures) in an attempt to enhance their worth.

Often an art expert evaluation is required to recognize the difference between the best fakes and authentic pieces. As a result, we recommend that new collectors learn from auction houses and dealers who are experienced in handling netsuke. The Forum of this website is also a great place to start one’s education, along with the acquisition of a few good books. Joining the International Netsuke Society allows a person to attend conventions and also interact with other collectors on a local basis for hands-on discussion with some of the world’s top authorities.

Don't the Japanese own all the great netsuke?

No, in fact most of the current greatest collections are outside of Japan. Netsuke were exported from Japan in large numbers starting in the last quarter of the 19th century. With the Meiji restoration in 1868, western dress was adopted in Japan and netsuke lost their raison d'être. Very large collections were built in England, France, and the United States. Today, many of the best collections are still in Europe and the United States either in private hands or museums.

What factors are involved when buying netsuke?

Authenticity

Determining authenticity is not that easy. The signature may be the easiest part of the whole carving to be faked, but even signs of age were successfully faked by some carvers at all times. As with most other art forms, all it takes to determine authenticity is to be able to accurately identify and match the age, the style, the school, the signature, the material, even the stroke and the artistry of different netsuke. This takes years of thorough studying and of handling of thousands of authentic netsuke to master.

Artistry/Skill of the Artist

Viewing a large number of netsuke shows us a broad range of skills of the artists who produced them. From the simplest “folk art” works to the Michaelangelo’s of the netsuke world we see every level of talent. Some collectors look for those artists who made very simple carvings, others complex and minutely detailed. One can find beauty in both and the skill a particular carver brings to either end of this spectrum is always open to debate. However, advanced collectors usually agree at least on the relative merits of a carving.

Condition

There is a good deal of disagreement about the importance of wear, chips, age cracks and restoration. There is no doubt that damage affects the value of a netsuke, but the extent of this depends on age and rarity, among other factors. Netsuke are expected to show some sign of wear but the wear on a netsuke should not be so far advanced as to devalue the piece. Most collectors will agree that cracks, minor chips, surface erosions, tiny repairs, and similar small defects are acceptable in direct relationship to the age of the netsuke.

Specific Artists/Schools of Carvers

The names Tomotada, Okatomo, Toyomasa, Tomiharu, Kaigyokusai, Kokusai, and Morita Soko are familiar to collectors and are highly sought after artists. Pupils of these top artists, their “schools” of followers, and subsequent carvers who worked in their style may be collected by those who cannot afford top level pieces. Seasoned collectors can differentiate styles/locales of netsuke production such as Kyoto, Osaka, Asakusa, Tokyo, Iwami, Hida and others. They may even “attribute” a specific netsuke to a well-known artist.

Rarity/Subject

Some subjects are infrequently encountered in netsuke and therefore more desirable. Such is the case with the mythical beast called a baku (which eats bad dreams). Others, such as the squirrel, even though not seen often don’t seem to draw the same level of interest. Some collectors specialize by collecting animals, legends, or mythical subjects, etc. They may be willing to pay more to fill a void in their collection or acquire a fine example of a subject they appreciate.

Price

Prices of netsuke vary greatly from a few hundred to hundreds of thousands of U.S. dollars. Top prices are frequently connected to a few well known artists. As with most other art objects, the value of a particular netsuke is based on a combination of intrinsic and extrinsic factors. In general the existence of a signature, unless proven to be authentic to a handful of the most famous master-carvers, does not have much influence on the value. Nor does the material. What matters most is the quality of carving, originality, rarity, and its artistic appeal. In the end beauty is in the eye of the beholder and when two willing buyers come together in the auction room sometimes the sky is the limit.